Living Thinking: Lecture 1 – From Spinoza to the Actualization of Freed Desire

a summary (and interpretation of) Chapters 1–4 of Rudolf Steiner’s Philosophy of Freedom

This post is an edited transcript of a video lecture from a series on Rudolf Steiner’s The Philosophy of Freedom, recorded for the Bay Area Waldorf Teacher Training Program. It covers Chapters 1-4, Conscious Human Action; The Fundamental Desire for Knowledge; Thinking in the Service of Knowledge; and The World as Percept.

Introduction: Revisiting Steiner's Core Questions

To begin, I'd like to do a review, which is customary for the Waldorf approach to education, and go back over the two questions—or the two aims—that Steiner opens the 1918 edition preface with. I'm sharing here an alternative translation of those two aims or questions so that we can have multiple takes in English. As Frederick Amrine, translating Steiner’s preface, writes:

I have attempted to show that there is a view of human nature which can provide support for all remaining knowledge. Moreover, I sought to indicate that with this view, full justification is gained for the idea of the freedom of the will, if only the realm of the soul is found within which free will can unfold.

That's quite different from the way the German was translated in the Michael Wilson version, where they're posed more as questions rather than presented as aims. But you get the idea, and I think it clarifies what was somewhat confusing in the Wilson translation: Is there some view of the human—of human nature—that can give us a support for all remaining knowledge? Some kind of confidence in knowing?

As I mentioned in the introductory lecture, where I went over a brief history of Western thought with respect to these two questions, there is a kind of echo of Descartes' "I think, therefore I am," and his insistence on thinking as the foundation for epistemology. But as we'll see, Steiner will make a different conclusion than Descartes does about the nature of thinking.

Chapter One: Conscious Human Action

Modernity and the Debate About Freedom

Steiner opens the text by acknowledging that the question of whether we are free or not has been argued passionately for and against by philosophers over the last 500 years. There are those who find it self-evident that freedom is a reality. And, on the other side, there are many proponents of the idea that everything unfolds according to necessity, those who are very much inspired by natural science.

Steiner's monism takes a more qualified stance on this question. For him, we can say that we are both unfree and also have the possibility of undertaking action that is consciously motivated, and so free—that we have the potential to become more free.

The Confusion of Freedom with Mere Choice

He then goes on to point out that many of the arguments against freedom have conflated consciously motivated action with the freedom of mere choice. Those who dismiss the idea of freedom when conflated with the idea of mere choice claim that there's always a most reasonable or necessary course of action in every circumstance that one might meet. Freedom, when construed as freedom of choice, is thus meaningless.

Steiner points out that this argument has been repeatedly rehashed since it was first lucidly set forth by Spinoza in his notion of free necessity—his vision of a world mechanism wherein the only free being is God, whereas everything else in the cosmos acts according to the causes that are outside of it, what ultimately root back to God.

One might ask Spinoza, "what really is the difference between a divinity that exists as free necessity and the creatures that are externally determined by this divinity?" But we'll leave that aside. Steiner then goes on to quote Spinoza, comparing human action—instancing the unfree thirst of an infant for milk or someone reacting out of hostility—as equal instances of any kind of human action, all of which are comparable to the trajectory that a stone takes when it's thrown or kicked. Necessary. Even if the stone were to be conscious like a human being and think that it's intending its own movement, in reality we all know it's moving according to necessary laws that are imposed upon it from without. And the same is true, Spinoza believed (says Steiner), for all human action.

Steiner finds Spinoza's articulation commendable because it's so simply expressed, making the error more evident. That error basically boils down to an unwillingness to make important distinctions between humans and animals or even stones. Steiner wants to make a distinction between consciously motivated actions and actions that we undertake out of some kind of compulsion.

Here's an example: Let's imagine a scenario wherein there is a person who grew up with parents that were really chaotic, whose behavior left their child feeling anxious a lot of the time. This child then grows up to be an adult who has what psychologists call “anxious attachment.” The individual has a hard time trusting other people and expects from everyone a similar kind of chaos that their parents modeled.

Let's say that when this person grows up they forge a relationship with a partner who has a very secure form of attachment, someone who is very stable. But this person—this first person that we mentioned—is bringing their former experience growing up with chaotic parents with them in their perception of the situation and so doesn't trust their partner initially, even though their partner time and time again shows them that they are trustworthy. This person with anxious attachment might be compelled—by their former experience, which they perhaps didn't even understand fully until they went to therapy—to excessively check with their partner, seeking some kind of reassurance: "You do love me, right? You do love me, right?"

But, in going to therapy, learning about this notion of attachment, and reflecting on their own experience growing up with chaotic parents, discovering the idea of

secure attachment” and what goes along with that—allow oneself to trust people who show you time and time again that they are trustworthy and not allowing oneself to be driven by thoughts that well up from the past—this person might then be motivated to intentionally transform their behavior to approximate the ideal of secure attachment (which can be quite hard when congealed into belief).

That's one example of consciously motivated action. The anxious person has discovered the concept of secure attachment and its corresponding features and consciously chooses to transform their existing behavioral patterns to achieve it. We could think of many other examples, some more mundane, some more grand. But if we refuse to make any distinction between consciously motivated and compulsory actions, we couldn't really make sense of the possibility for change—unless the change (as opposed to the potential for change) was written in the stars from the beginning, which, in my opinion, makes the notion of creative change meaningless. Moreover, if everything was already determined, would be really be able to be conscious of the possibility or potential of otherwise?

The Question of Characterological Determination

This leads us into another argument against freedom Steiner entertains, coming now from a philosopher who was alive during the same time as him—someone who he had a lot of admiration for—Edward von Hartmann and his notion of characterological determination. To give an example of this concept, we could draw on the premodern theory of temperaments. I might say "I'm a sanguine, I always act this way," because I have this character—or maybe, if you're into astrology, "I'm a Libra, I'm like this," or maybe, if you're into Myers-Briggs, "I'm an ENFP, I have such and such tendencies"—any kind of characterological typology that would allow us to define ourselves archetypally, accounting for how we’re inwardly determined to act according to certain patterns of motivations. For Hartmann, this means we're not really free—but actually determined from within as well as from without.

"Here again," as Steiner writes, "the difference between motives which I allow to influence me only after I have permeated them with my consciousness and those which I follow without any clear knowledge of them is absolutely ignored."

This permeation in consciousness that Steiner refers to will be bound up with our capacity to think freely. "But what does it mean to have knowledge of the reasons for one's actions?" Steiner asks.

Beyond Abstract Reason and Animal Passion

He then goes on to acknowledge some prevailing ideas of how people often think about this question. As he writes, "it is said that man is free when he is controlled only by his reason and not by his animal passions. Or again, that to be free means to be able to determine one's life and actions by purposes and deliberate decisions."

Abstractly reasoned action, however, could just be another form of compulsion—this time coming from the mental pole, or to use Steiner's later, more concrete (or pictorial/imaginative) terminology, the head: bound up with memory pictures which inform the ways in which one was punished or taught abstractly what is "right" or "wrong" to do. This “head” content constitutes another kind of unfreedom, similar to being driven by unconscious compulsions that may have more to do with instinct.

The Problem of Will and Motive

Steiner then proceeds to consider another argument against freedom, this time from Robert Hamerling, who says, "Man can certainly do as he wills, but he cannot want as he wills, because his wanting is determined by motives,” and, concluding a bit further, “therefore, it is quite true that the human will is not free inasmuch as its direction is always determined by the strongest motive."

So not only is there a conflation of desire with motive, but as Steiner says, “here again only motives in general are mentioned without taking into account the difference between unconscious and conscious motives.”

Over and over again, Steiner is insisting on the importance of being able to make distinctions between different kinds of actions, at least for humans. "The primary question," Steiner says, "is not whether I can do a thing or not when a motive has worked upon me, but whether there are any motives except such as impel me without absolute necessity."

So—are there motives that I can consciously select for myself? Am I forever doomed to be anxiously attached or can I choose or aspire to act in such a way, or to only humor thoughts conducive of trust, that will move me toward secure attachment? And if so, is something else doing that for me, or is it truly of my own volition?

The Human Capacity for Rational Thinking

Steiner then goes on to make a distinction between human beings and animals by claiming that human beings exercise rational thinking.

And someone might argue, "well, how can we know that humans have rational thinking and other animals don't?"

For those who are familiar with Steiner's expansion of Goethe's method, one might argue that you could look at the human form and read this capacity for rational, abstract thinking off of it. To the extent that, unlike other animals, our hands are less specialized—left open, without claws or fins—you could say, as Plato did 2000 years ago, that we are left unfinished and in need of the supplement of culture in order to survive. Humans must have a kind of technological purchase on the world, must create our own tools—a capacity that, beyond the most rudimentary forms, abstract thought is necessary for. So we could think of the capacity for rational thinking as also this expression of our being separate from the world—having this experience of being separated out from it and yet still one with it—whereas other creatures, with their instinctual understanding of how to inhabit the world, are more continuous with their environs.

The Implications of Human Distinctiveness

He then goes on to consider the Spinozist (he claims) conflation of human willing with animal behavior, and even conflating animal behavior with the movement of a stone. Steiner, even though he doesn't dwell on it here, would make distinctions between all of those—not claiming that the donkey, for instance, is just some kind of necessary motion moving like a rock, much less a human.

Because if human beings were so determined, we wouldn't be concerned with justice. We wouldn't think it right to deal any kind of punishment or reprimand to people who have done something wrong.

We also wouldn't treat other animals differently than we treat other humans. Why is it that we don't hold a dog or a cat accountable for killing something in the same way that we would a human?

That's an important question to ask if we want to shore up the reality of ontological differences. Steiner reiterates once more that there is an unwillingness to recognize the distinction between consciously motivated actions and compulsory actions. What about an action for which the reasons are known? This leads us to the question of the origin and meaning of thinking, which he will take up throughout the rest of the book.

The Integration of Thinking and Feeling

In consciously motivated—thoughtfully considered—action we now have a hint at the first question posed in the preface of the 1918 edition: is there something that we can understand about human nature that can give us some kind of confidence in the possibility of gaining genuine knowledge of the world—and also knowing whether or not we can freely act in it?

But then Steiner wants to qualify this ratiocentric characterization of human nature and says, "I am very far from calling human, in the highest sense, only those actions that proceed from abstract judgment." This is where desire, feelings, and love come in. For Steiner, thinking is always bound up with feeling, and thinking can be the guide for ever nobler feelings, for transforming desires that maybe aren't so good for us into desires for something higher. With thinking, for instance, we might be guided through transforming the inner turmoil and suspicion characteristic of anxious attachment toward feelings of trust and beneficent consideration.

In the anthroposophical world there are what are colloquially called the "six basic exercises," exercises, you might say, for spiritual-psychic hygiene, and one of them is called "positivity," which basically entails intending to see the good in everything—an intellectual, imaginative activity that gradually begins to transform one's habitual feeling life. As Steiner writes in The Philosophy of Freedom:

"Whenever it is not merely the expression of bare sexual instinct, it depends on the mental picture we form of the loved one—how we think of them, how we feel towards them. And the more idealistic these mental pictures are, just so much the more blessed is our love."

We'll get into this in more depth later on, but when he says "mental picture," think (in the case of the “positivity” exercise) of a combination of our cumulative memory-image of someone that we know and our thinking about them—our capacity to, through observation, recognize good things about them and to focus only on that.

“And the more idealistic these mental pictures are, just so much the more blessed is our love. Here too, thought is the father of feeling. And it's said that love makes us blind to the failings of the loved one, but this can also be expressed the other way around—namely, that it is just for the good qualities that love opens the eyes. Many pass by these good qualities without noticing them. One, however, perceives them—or another perceives them—and just because he does, love awakens in the soul. What else has he done but made a mental picture of what hundreds have failed to see? Love is not theirs because they lack the mental picture."

This emphasis on the mental picture also helps us to see that, when Steiner's talking about living thinking, he's also talking about what we call imagination—a kind of active thinking that includes image, that is to say, our internalization of the world in memory and our thinking about them—thinking which then weaves with and transforms—those memory-images.

Chapter Two: The Fundamental Desire for Knowledge

The Human Condition of Separation and Longing

Steiner opens Chapter 2 with the following quotation from Goethe's Faust Part I (Scene 2, lines 1112-1117):

"Two souls reside, alas, within my breast, And each one from the other would be parted. The one holds fast, in sturdy lust for love, With clutching organs clinging to the world; The other strongly rises from the gloom To lofty fields of ancient heritage."

Here Goethe captures something essential about human experience—at least for most of us as we are presently constituted today: the experience of being a self over against a world that we feel that we are somehow a part of, but also feel that we don't fully know, or understand, and yet feel compelled to. A feeling of incompleteness, of mystery. For Steiner, desire is the expression of this incompleteness, but yet also of still somehow being related to, being one with, the world—desire as the yearning to overcome that gap.

The pursuit of knowledge—or the desire for knowledge—is one manifestation of this more basic situation of separation, an inchoate sense of belonging, and the movement to realize a complete and conscious unity.

The Uniqueness of Human Desire

Someone might offer the criticism, “well, animals have desires too, right?” But it might be more accurate to say that animals have needs they seek to satiate. We humans have needs too of course, but when we speak of desire with respect to human beings, there's something almost limitless about it, something about it that reflects an inchoate awareness of the infinite. I think something like addiction, which animals only really fall into in proximity to humans, is an expression of this human intuition of the infinite.

The pursuit of knowledge itself may be read as an inchoate awareness of the infinite and the potential to encompass the whole through conscious lucidity (knowledge)—or at least to deepen toward it in an ever-ongoing adventure in knowing the world as an actual being—to know God, perhaps.

When we relate to the world as the revelation of a divine being, we don't fall under the illusion that we could ever completely know it—because we never fall—or shouldn't fall—under the illusion that we could ever completely know the depths of another human being, or any other creature.

The I-World Polarity

This overall situation of separation yet belonging generates the I–world polarity.

For Steiner, following his German idealist predecessors, the "I,"—what we use as the first-person pronoun—has a kind of metaphysical meaning to it. It's ontological status is continuous with the way we use the pronoun in everyday speech, but when he says "I," he also implies that aspect of ourselves—of our subjectivity, of our consciousness—that is the observer. The “I” is not essentially identified with the personality, rather, it has the capacity to objectify and observe the personality, or our characterological disposition. To use premodern terms, it might be correct to identify the "I" with the spirit, the personality with the soul.

And we come to consciousness of that distinction through counterpointing the world, which, as we'll see further on, includes the relatively given (though malleable) character of our personality, or idiosyncrasies of feeling and preference.

Philosophical Approaches to the I-World Problem

Steiner then goes on to discuss ways in which philosophers have attempted to grapple with this polar I-World polarity in metaphysics. Metaphysics is that branch of philosophy which tries to describe the most fundamental character of the world, the contours of experience that most of us take for granted. For Steiner in this text, the metaphysical dualist perspective assumes that the "I" is the representative in our experience of spirit and the world that we experience without as representative of matter—and posits that these poles are irreconcilable.

Monist perspectives by contrast, either reduce all to spirit or all to matter, or to some kind of combination of both while maintaining their incompatibility and so amounting to a form of dualism.

The Inadequacy of Materialism

Interrogating these various positions, Steiner begins by insisting that materialism can never offer a satisfactory explanation of the world, for every attempt at explanation must begin with the formation of thoughts—a process that necessarily involves the subject; a spiritual process—about the phenomena of the world which are taken to be exclusively material. This criticism might seem counterintuitive to many of us who have been raised to think in materialistic terms because when we're raised to think that way we unconsciously assume that matter or the material world is more fundamental than consciousness or spirit. And even if we don't consciously think that way, we might still act that way (Owen Barfield referred to this latter tendency as R.U.P., or the "residues of unresolved positivism").

But, as Steiner points out, materialism is inadequate because all theory—every time we begin to cook up some kind of explanation of the world—depends upon the transubjective, spiritual activity of thinking. Materialism therefore presupposes a spiritual activity that it can't fully account for, so there's some kind of contradiction here in claiming that thinking is less fundamental than the material world.

The Inadequacy of Spiritualism

Spiritualism, on the other hand, doesn't work either because the very possibility of knowledge—or knowing the world at all—relies upon (at least as we experience it now) some relationship with a material or outer world that does not (usually) respond like a genie to the will of our imagination. The same goes with action: as we experience life now, our thoughts can only translate themselves into action through the body, or at least by taking some kind of effect in the physical world. That's at least what Steiner's claiming here. He might have a more complex way of framing things later on in his esoteric work.

“It is we ourselves who break away from the bosom of nature and contrast ourselves as 'I' with the world," claims Steiner at the end this chapter. What he's saying here is that this dualism—or this opposition between spirit, identified with the "I," and world—is something that is not ultimately characteristic of the world itself, but is something that we introduce through our “mental organization,” as he'll put it later in the book. He then draws once more on his notion of desire as the reflection of our actually being one with nature and feeling, compelled to move towards some kind of reunion with it. As he writes:

"We must find the way back to her again. A simple reflection can point this way out to us. We have, it is true, torn ourselves away from nature, but we must nonetheless have taken something of her with us into our own being. This element of nature in us we must seek out, and then we shall find the connection with her."

And then, further on, writes:

"This element of nature in us we must seek out, and then we shall find the connection with her once more. We can find nature outside us only if we have first learned to know her within us. What is akin to her within us must be our guide. This marks our path of inquiry."

Chapter Three: Thinking in the Service of Knowledge

The Two Phases of Knowing

Steiner opens Chapter Three by making a distinction between two different phases in the act of knowing. The first is observation—attending to what is given to us by experience—the objects—which could also include, as we'll see, our own feelings and prior thoughts. And the second phase is our contemplative (thoughtful) reflection upon and analysis of that experience. Through analysis we break experience down into parts, different concepts, and then, when we articulate explanations, can illuminate connections between things that were hitherto only implicit in our experience.

Implied in what I just described is a distinction between that which is given in observation—that which does not depend upon us—and the active process of analysis or contemplative reflection which does require our activity, something that we have to intend and are therefore aware of doing.

"As surely as the occurrence goes on independently of me," writes Steiner, "so surely is the conceptual process unable to take place without my assistance."

At this point Steiner wants to bracket the question as to whether or not this thinking activity that seems to be of our own intention—our own will—is actually ours or not. He then emphasizes something that he'll go on to repeat: that concepts, what allow us to connect the disparate aspects of an observation together so that we can come to understand it, are not given immediately in observation.

In the opening part of the chapter, he brings the example of shooting a billiard ball—the trajectory that it takes in space—and then describes the process of reflecting upon what was observed afterwards with certain concepts that one would have already gained through personal experience, studying science, conducting experiments—concepts like velocity, elasticity, roundness—and that these, combined in a certain way, can yield an understanding of what would happen if a person was standing in a particular place, shooting the ball a particular way. Equipped with such concepts, one might even be able to predict the outcome of that situation without actually observing it.

With this example, Steiner illustrates that what thinking supplies us is an understanding of the otherwise mysterious connections between the various constituents of what we observe with our senses.

The Fundamental Polarity of Human Experience

Steiner then goes on to describe this continuum of observation and thinking—you could think of it as a dynamic form, like a lemniscate—as being the most basic polarity from which all of the metaphysical dualisms that philosophers have come up with arise: "Observation and thinking are the two points of departure for all the spiritual striving of man, insofar as he is conscious of such striving," writes Steiner.

This statement exemplifies the way in which Steiner's approach to philosophy is a phenomenological one. He wants to start in human experience. All of the dualisms that people have come up with, like matter versus spirit, start from this experienced polarity of observation and thinking. And in this dynamic, observation always comes first and thinking second—at least when we're talking about thinking as the reflective activity on those observations.

The Scope of Observation

"Everything that enters the circle of our experience," writes Steiner, "we first become aware of through observation. The content of sensation, perception and contemplation, all feelings, acts of will, dreams and fancies, mental pictures, concepts and ideas, all illusions and hallucinations are given to us through observation."

Significantly, Steiner here expands the notion of perception beyond the senses and what we experience through our feelings to include our reflective, thinking activity—a kind of observation of past ideas and concepts. But whereas observation of things and events, and thinking about them, are everyday occurrences filling up the continuous current of my life, writes Steiner, "observation of the thinking itself is a kind of exceptional state."

The Exceptional State of Observing Thinking

"We must be quite clear about the fact that," as he continues further on, "in observing thinking, we are applying to it a procedure which constitutes the normal course of events for the study of the whole rest of the world content—everything that we feel and experience without—but which in the normal course of events is not applied to thinking itself."

In other words, when we're observing the world, we're typically more aware of what we're observing—not the fact that we are also simultaneously thinking—or contributing concepts to—what we're observing. We are not typically conscious of the fact that our thinking is participating in the constitution of what we perceive.

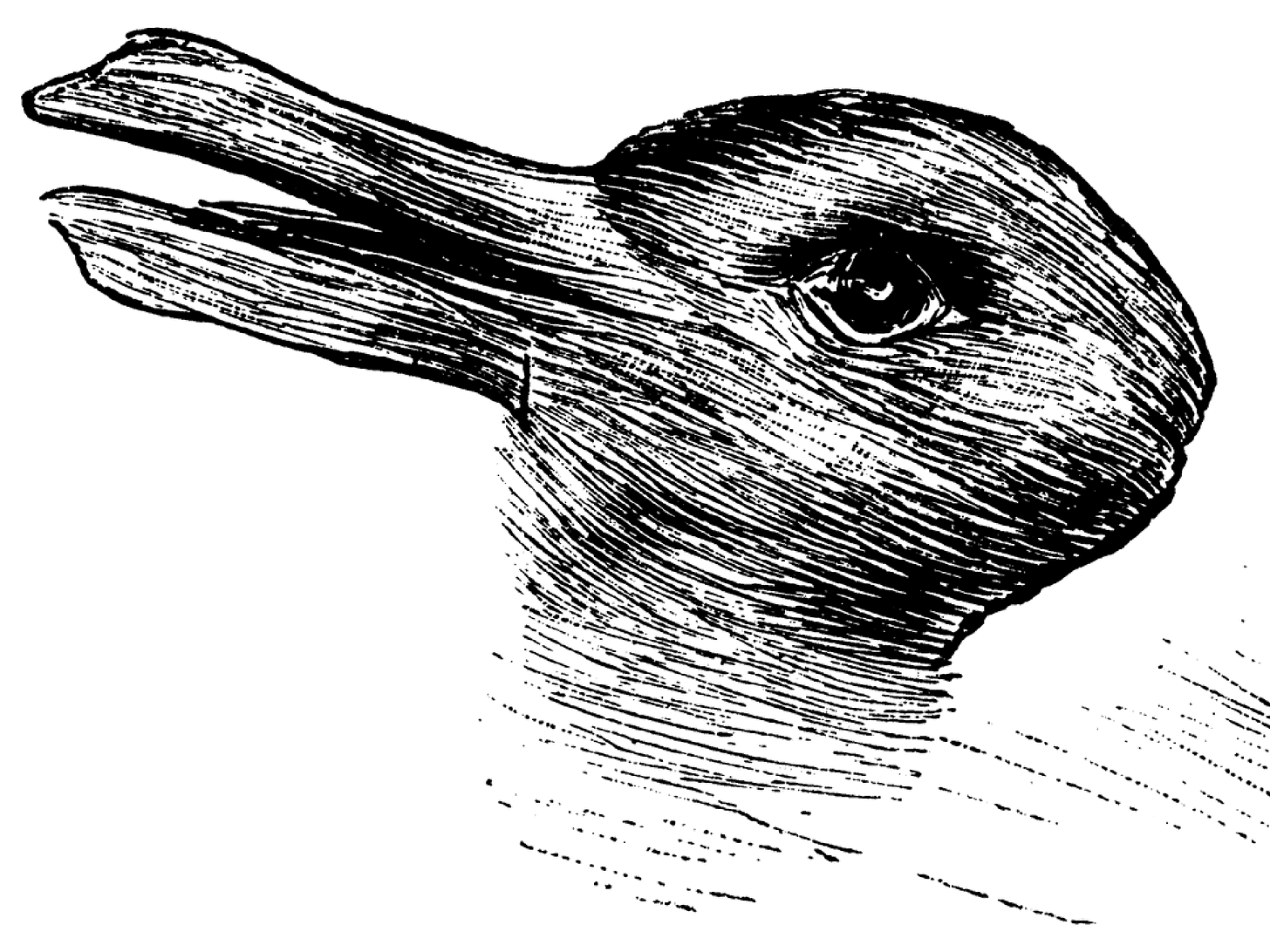

In the introductory lecture I shared an image that helps viewers to become conscious of that fact. Gazing at it, we could perceive one of two things:

A rabbit looking to the right or a duck looking to the left.

Working with images like this can help make us aware of the fact that, when we are perceiving something that we recognize as a distinct thing—something that we could name—we are also at the same time contributing thoughts to the sense datum such that it becomes an actual object of perception. To see the duck, you have to intend the concept; if you want to see the rabbit, you have to cease intending the duck and instead intend the concept of the rabbit.

Conscious awareness of this thinking activity at work in perception is what Steiner refers to as the "exceptional state." He also refers to it as contemplative observation, living thinking, or imagination. Observation and thinking then become an undivided continuum, an ever-deepening adventure of perception. For those interested in Owen Barfield, Goethe, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, we could describe it as conscious figuration, or a systematic approach to making the primary imagination a conscious experience.

Distinguishing Thinking from Feeling

Having established the unique character of thinking, Steiner turns to address a potential objection: If thinking and feeling both involve a relationship between subject and object, why can one not claim that feeling provides an equal pathway for knowledge and free (conscious motivated) action?

“A feeling of pleasure," he writes,

"does not stand at all in the same relation to its object as the concept formed by thinking. I am conscious, in the most positive way, that the concept of a thing is formed through my activity. Whereas pleasure is produced in me by an object in the same way as, for instance, a change is caused in an object by a stone which falls on it. For observation, a pleasure is given in exactly the same way as the event which causes it. The same is not true of the concept. I can ask why a particular event arouses in me a feeling of pleasure—but I certainly cannot ask why an event produces in me a particular set of concepts. The question would be simply meaningless."

What Steiner means here is that intuitions or concepts are not given in observation, but rather require us to reflect upon or analyze what was observed in order to conceptually distinguish the different facets of that experience. An increase of concepts requires time. One only arrives at the specific variation of the more general concept flower, of a rose, for instance, through having repeatedly encountered the distinct features which accompany the appearance of it, thereby achieving the capacity to conceptually distinguish between a rose and another species of flower. Continual observation is necessary for us to be able to conceptually distinguish these particularities, but we can't derive their concepts from our sense perception itself.

The feeling of pleasure—or any other kind of feeling—by contrast, is something that issues more or less from the objects themselves—and is also, as we'll see, a factor of our personality (i.e., preference), which is not the same as what Steiner refers to as the "I," or the observer, which participates in the process of consciously making conceptual distinctions.

As Steiner writes, "When I say of an observed object, 'This is a rose,' I say absolutely nothing about myself. But when I say of the same thing that it gives me a feeling of pleasure, I characterize not only the rose, but also myself in relation to the rose."

We could clarify this by pointing out that—though it might be surprising—there may be some people for whom the smell of a rose, or the sight of a rose, isn't a pleasurable experience. The concept of the rose, the fact that this is a rose, however, will be the same for everyone. How we each individually feel about it—that is particular.

The Paradox of Observing Our Own Thinking

This leads Steiner to articulate a fundamental paradox about the nature of thinking itself. He writes:

"While I am thinking, I pay no heed to my thinking, which is of my own making, but only to the object of my thinking, which is not of my making. I am moreover in the same position when I enter into the exceptional state and reflect on my own thinking. I can never observe my present thinking. I can only subsequently take my experiences of my thinking process as the object of fresh thinking."

We can observe our past thinking, but we cannot simultaneously think and observe that very same thinking process. There's always a temporal gap between the thinking activity and our observation of it.

Steiner then draws on Genesis, where God is said to have created the world in six days and then called it good, as a picture for expressing this. Just as God could only evaluate the creation after it was complete, we can only observe our thinking after it has occurred, making it an object of fresh contemplation. As Steiner writes,

“What in all other spheres of observation can be found only indirectly—namely the relevant context and the relationship between individual objects—is, in the case of thinking, known to us in an absolutely direct way. I do not, on the face of it, know why thunder follows lightning from observation alone, but I know directly, from the very content of the two concepts, why my thinking connects the concept of thunder with the concept of lightning.”

Against Materialist Reductionism

Steiner addresses those who would say that our tendency to connect these concepts is just a factor of our brain processes. He responds:

"What I observe about thinking is not what process in my brain connects the concept lightning with the concept thunder, but what causes me to bring the two concepts into a particular relationship. My observation shows me that in linking one thought with another, there is nothing to guide me but the content of my thoughts. I am not guided by any material processes in my brain."

Remember that at the start of the book, Steiner asks whether we can identify something essential about the human being that can serve as the starting point for solid knowledge about the world. For him, this is thinking and our observation of it, “For he observes,” as Steiner writes, “something of which he himself is the creator."

And further: "A firm point has now been reached from which one can, with some hope of success, seek an explanation of all other phenomena of the world."

Here we hear an echo of Descartes. Of Descartes' "I think, therefore I am," Steiner says: "All that he had any right to assert was that within the whole world-content, I apprehend myself in my thinking as in that activity which is most uniquely my own — or at least it seems to be. It seems to be dependent on our volition."

The difference between the human subject as a thinking subject and all other objects is that their essence—at least for us as creatures who can come to understand things—must be understood in connection with other things. But the starting point for knowing the world begins with our own thinking activity.

The Self-Reflective Nature of Thinking

When I think about thinking, I'm reflecting on a process that itself gave rise to what I'm reflecting upon. For example, when practice what Steiner referred to as the

concentration or “control of thought” exercise, this is a kind of intensified awareness of what's happening all the time when we're perceiving the outer world. Through regular practice of this exercise we can become more aware of the productive activity that gives rise to fresh thoughts that well up, as if from a spring, all the time. When concentrating our thought on the pencil—the pencil is a cylinder, the pencil has a pink eraser— for example, we observe how these thoughts well up from our intending to think about the object we're focusing on.

Creating Nature Through Knowing

This activity directly bears on Steiner’s quotation of the seemingly enigmatic claim from his philosophical forefather Friedrich Schelling that "To know nature means to create nature."

"If we take these words of this bold nature philosopher literally,” says Steiner, “we shall have to renounce forever all hope of gaining knowledge of nature — because then we would have to create nature before we could know it. But then we would have to know it in order to create it in the first place."

Instead, Steiner argues that knowing nature requires our creative activity—creating before knowing—which we experience in the act of thinking.

"Were we to refrain from thinking until we had first gained knowledge of it, we would never come to it at all. We must resolutely plunge right into the activity of thinking so that afterwards, by observing what we have done, we may gain knowledge of it. For the observation of thinking, we ourselves first create an object. The presence of all other objects is taken care of without any activity on our part."

What's implied here is that there is an initially inchoate thoughtfulness or intelligence (wisdom!) inherent in what we experience through observation, which we can illuminate further upon reflection later—and, perhaps through practicing Steiner’s method, gradually experience immediately through contemplative observation.

Addressing Suspicion of Thinking

Steiner addresses those who would say that what we unconsciously contribute to perception is different from what we actually experience, and therefore question the veracity of conscious thought. He acknowledges that every thinker is situated and therefore limited in what they can think. But with reference to our situatedness—our particularity, our position in time and space, and our cultural conditioning—such thoughts are still valid.

This suggests that to have a more comprehensive picture of the whole, we need to bring many perspectives together—which is what science and all disciplines taken together in the transdiscplinary endeavor of philosophy aspires to do.

Another criticism asks why one would start with thinking rather than consciousness, since thinking presupposes consciousness. Steiner replies: "To this I must reply that in order to clear up the relation between thinking and consciousness, I must think about it."

"We must first consider thinking quite impartially, without reference to a thinking subject or a thought object. For both subject and object are concepts formed by thinking. There is no denying that before anything else can be understood, thinking must be understood — because thinking is that by which we make things understood, that through which we understand things. Whoever denies this fails to realize that man — or the human being — is not the first link in the chain of creation, but the last."

He doesn't mean this in a Darwinian sense, rather,

“As long as philosophy goes on assuming all sorts of basic principles — such as atom, motion, matter, will, or the unconscious — it will hang in the air. Only if the philosopher recognizes that which is last in time as his first point of attack can he reach his goal. This absolutely last thing at which world evolution has arrived is in fact thinking."

What he means is that the human is the creature that turns back and wakefully looks upon the whole dreaming process of natural evolution. Thinking is the means by which we do so.

Steiner then also addresses those who would question whether thinking can be correct or incorrect, characterizing it as merely a survival mechanism without purchase on reality. But he argues that thinking is self-evident. The rose is a rose. There may be different words for the concept in different languages, but the concept itself is a fact of thinking.

The question is not whether thinking is right or wrong, but whether we're applying thinking correctly.

Chapter 4: The World as Percept

Understanding Concepts and Intuition

Steiner opens this chapter by exploring what concepts are and how we intuit them:

“When someone sees a tree, their thinking reacts to the observation. An ideal element is added to the object, and they consider the object and its ideal counterpart as belonging together—the ideal counterpart being that which grants it meaning in a larger context. When the object disappears from their field of observation, only the ideal counterpart remains. This is the concept of the object. The more our range of experience is widened, the greater becomes the sum of our concepts. But concepts certainly do not stand isolated from one another. They combine to form a systematically ordered whole."

This is characterization is important because it shows that concepts by themselves are always abstract. If we recall Steiner's characterization of the human as bound up with nature but separated from her—and yet bringing something of her with us that may guide us back into unity—then it becomes evident how our aspiration to expand the scope of our concepts is an essential activity for reuniting ourselves with the world.

Paradoxically, that which has helped separate us from nature and awaken self-consciousness is also the means by which we reunite and retain self-consciousness.

Steiner emphasizes that, contra Hegel, his starting point is thinking, not the concept. Rather than treating concepts as abstract units that build up to a picture of the world, the growth of concepts enhances our capacity to read the dynamic meaning in the world—to participate in the speaking Life of the world. Steiner is inviting us into a literacy of the world and of experience itself. In continuity with observation coming prior to thinking, he says that concepts come with experience. Knowledge is developmental—bildung. In this vein Steiner will claim that

"Human consciousness is the stage upon which concept and observation meet and become linked to one another. In saying this, we have in fact characterized human consciousness: it is the mediator between thinking and observation."

As the mediator of these activities, we become self-conscious:

"Because we direct our thinking upon our observation, we have consciousness of objects. Because we direct it upon ourselves, we have consciousness of ourselves — or self-consciousness. Human consciousness must of necessity be at the same time self-consciousness, because it is a consciousness that thinks. For when thinking contemplates its own activity, it makes its own essential being as subject into a thing as object."

Thinking as Trans-Subjective Activity

In one of the most quoted parts of the book, Steiner shows his continuity with pre-modern philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, who held that there was cosmic thinking that humans participate in. Even though human subjects participate in thinking and are thereby self-conscious, thinking actually lies beyond subject and object:

"It produces these two concepts just as it produces all others. When therefore I, as thinking subject, refer a concept to an object, we must not regard this reference as something purely subjective. It is not the subject that makes the reference, but thinking. The subject does not think because it is a subject; rather, it appears to itself as a subject because it can think. The activity exercised by man, or the human being, as a thinking being is thus not merely subjective. Rather, it is something neither subjective nor objective, which transcends both these concepts."

We could say it's trans-subjective or trans-objective. It's what mediates between them. It's something we participate in, something that is part of the cosmos.

The world is thus word-like—it is both image (something we can perceive through our senses) and also has a conceptual (semantic, intelligible, inward, meaningful) aspect that allows us to understand it. Like words on a page—there are the marks we perceive and the meaning, which is the conceptual relations between words that we contribute because we are literate.

"I ought never to say that my individual subject thinks, but much more that my individual subject lives by the grace of thinking," writes Steiner. "Thinking is thus an element that leads me out beyond myself and connects me with the objects — but at the same time, it separates me from them, inasmuch as it sets me as subject over against them."

Thinking is this activity we can participate in. This capacity is bound up with our rift from being one with the natural world, but we also have potential to consciously reunite with the world through it—through a participatory form of knowing, not merely abstract knowing.

The Thought Experiment of Pure Observation

What is thinking directed at? Objects—but how do those come into our awareness? Steiner says: "In order to answer this question, we must eliminate from our field of observation everything that has been imported by thinking. We must imagine that a being with fully developed human intelligence originates out of nothing and confronts the world."

This is a thought experiment for clarifying the process of knowing the world—we never actually experience the world like this, because we're always starting somewhere with experience.

"What it would be aware of before it sets its thinking in motion would be the pure content of observation,” Steiner imagines, “which is not an actual experience. But for the sake of trying to understand this process, we can abstractly describe it or imagine it. The world would then appear to this being as nothing but a mere disconnected aggregate of objects of sensation — so just chaos. Colors, sounds, sensations of pressure, of warmth, of taste and smell — also feelings of pleasure and pain."

This aggregate is the content of pure, unthinking observation. Just chaos—we wouldn't recognize anything or illuminate the distinct relationships between things.

For the sake of clearly distinguishing between thinking activity and what thinking activity is brought to—before it saturates those objects of observation and allows us to recognize them as things—for example, in the duck-rabbit image: without the concepts of duck and rabbit, this would appear as chaos, Steiner deploys the term “pure percept.”

"It is, then, not the process of observation, but the object of observation, which I call the percept." Objects of observation, as I have repeated, can include prior thoughts. A thought could be a percept as well—it doesn't just have to be something we perceive through our senses.

The more we experience, the more observations we collect, the more we have to continually correct our initial percept of the world, or worldview:

"Every extension of the circle of my percepts compels me to correct my picture of the world. We see this in everyday life as well as in the spiritual development of humankind."

Throughout the text, Steiner refers to the naive person or naive realism—the idea that the world is just how we experience it. For example, the sun revolves around the earth. This was the naive understanding, based basic observation of the diurnal cycle, until centuries of conceptual reflection arrive at a correction of the world percept, which then encouraged us to historically distrust what the senses disclose.

Why are we compelled to make continual corrections to our observations? Because we're limited—spatially (limited by our place of observation, the mathematical limitation of our position) and qualitatively (according to our physiological, organismic, sense-perceiving, and cultural constitution).

Perception is subjective, but thinking can help us reach for more universal or consensus understanding between our uniquely situated experiences.

This acknowledgment—that perception depends upon an organism—has led philosophers like George Berkeley to articulate a metaphysics assuming the world of our experience is made up of mental pictures, and that objects are only there when there's a subject to perceive them.

Steiner isn't satisfied by this, because he wants our mental pictures to correspond to something real in the world—because he wants to hold out for the reality of having actual knowledge of the world, though admittedly limited and provisional.

Views like Berkeley's are fine if we focus on the fact that our organization contributes something to what is perceived. But to get more insight into the actual things-in-themselves that correspond to our mental pictures, Steiner thinks we have to ask more about what happens to us in this process of perception.

The Self-Percept

"In the process of perception, I perceive not only other things, but also myself. The percept of myself contains, to begin with, the fact that I am the stable element in contrast to the continual coming and going of the percept pictures."

We could become conscious of ourselves in the act of perception. While looking at a fern, we can include within our observation of the fern our self-observation of ourselves observing the fern. But we don't usually add ourselves to our observations. We don’t usually abide in the exceptional state. “If,” imagines Steiner,

“we add to our observation of a tree the observation of ourselves observing the tree, Then do not merely see a tree, but I also know that it is I who am seeing it. I know moreover that something happens in me while I am observing the tree. When the tree disappears from my field of vision, an after-effect of this process remains in my consciousness: a picture of the tree. This observation has become associated with myself during observation. Myself has become enriched. Its content has absorbed a new element—the element I call my mental picture of the tree. I should never have occasion to speak of mental pictures did I not experience them in the percept of my own self."

Here Steiner introduces mental pictures and the notion of the self-percept, which is modified by our observation of objects outside us. That's how we can know there is something out there that corresponds to our mental pictures—because there's a change in us that corresponds to something essential about them, something that was not hitherto a part of our inner world, or self perception.

In the Waldorf approach this theory of perception is put into practice through the creation of main lesson books, wherewith, instead of abstractly receiving concepts through lecture alone, students internalize their knowledge in mental pictures by creating their own textbooks of what is being learned.

This pedagogical method also emphasizes leading students through experiences or observations before providing them the concepts corresponding to the phenomenon in question (i.e., experimenting with a prism before describing the physics of light). Having made those observations, they now have memory images (mental pictures) within them with latent conceptual connection that can be drawn out of them later by teachers, rather than giving them concepts prematurely.

By theorizing the mental picture between the object and the subject and its modification of the self percept, Steiner finds a bridge between subjective experience and the objects in-themselves.

"I perceive the mental picture of what was experienced of the thing-in-itself, in myself, in the same sense as I perceive color, sound, etc. in other objects. I am now also able to distinguish these other objects that confront me by calling them the outer world, whereas the content of my percept of myself I call my inner world."

Steiner is critical of philosophers like Kant who overemphasize the modification or mental picture that arises in our relationship with the world at the expense of the objects that correspond to those mental pictures. Kant was concerned with articulating a philosophy in accord with new discoveries by modern science, and the skepticism regarding the value of human subjectivity and sense perception in pursuit of knowledge—especially given the Copernican Revolution, where there was slow embrace of the idea that the earth revolves around the sun, rather than the reverse.

Kant tries to transpose this into a characterization of the process of knowledge by claiming that all we can really know with confidence is our mental pictures. Later reductionist-oriented scientists and philosophers would claim that what's really going on is not what we experience, but interactions at the level of particles (physics) or various processes of our organism (physiology). These processes are claimed to be what is really real. But all of this presupposes that the sense organs themselves are fundamental in the same way that the naive realist would believe that the eye really sees the sun as it is.

Summarizing this view with respect to observation of a trumpet, Steiner writes:

"the visual, tactile and auditory sensations which the soul then combines into the mental picture of a trumpet. It is just this very last link in a process, the mental picture of the trumpet, which for my consciousness is the very first thing that is given. In it, nothing can any longer be found of what exists outside me and originally made an impression on my senses. The external object has been entirely lost on the way to the brain and through the brain to the soul."

But Steiner asks: what about the sense organs?

“Are they not also percepts? Just as we're aware of things we perceive through our sense organs, we're also aware through observation that there are sense organs, which we have mental pictures of. I must henceforth treat the table, of which formerly I believed that it acted on me and produced a mental picture of itself in me, as itself a mental picture. But from this it follows logically that my sense organs and the processes in them are also merely subjective. I have no right to speak of a real eye, but only of my mental picture of the eye. Exactly the same is true of the nerve paths and the brain process, and no less of the process in the soul itself, through which things are supposed to be built up out of the chaos of manifold sensations. If, assuming the truth of the circle of argumentation, I run through the steps of the act of my cognition once more, the latter reveals itself as a tissue of mental pictures, which, as such, cannot act on one another. I cannot say that my mental picture of the objects acts on my mental picture of the eye, and that from this interaction my mental picture of color results. Nor is it necessary that I should say this. For as soon as I see clearly that my sense organs and their activity, my nerve and soul processes, can also be known to me only through perception, the train of thought which I have outlined reveals itself in its full absurdity."

In future chapters, Steiner will say: we can't explain percepts by reference to other percepts—we can only explain the relationship between percepts. There's this whole chain of percepts—from the objects perceived without, to the sense organs that perceive them, to the processes that somehow leap into what we experience in our soul experience. These are all percepts, but they can only be explained in their interconnection by thinking.

Final Critique of Critical Idealism

Of critical idealism—the view Steiner associates with Kant and philosophies based on criticism of naive realism—critical idealism thinks it advances beyond naive realism by claiming that, in actuality, the world is just our mental picture. We don't really experience things as they are.

But as we’ve seen above, this view presupposes, in a naive realist fashion, that the sense organs aren't mental pictures:.

"It wants to prove that percepts have the character of mental pictures by naively accepting the percepts connected with one's own organism as objectively valid facts. And over and above this, it fails to see that it confuses two spheres of observation between which it can find no connection."

Steiner closes the chapter with this refutation, claiming that because this variant of critical idealism refuses to stay within thinking in its effort to explain things—and instead attempts to explain perceptions through other perceptions—it can't offer a satisfactory answer to the questions which inquire after the nature of the relationship between our mental pictures and the objects of perception, or the "things-in-themselves," that they correspond to.