Toward an Anthroposophical Astronomy

Reflections on Rudolf Steiner's "Interdisciplinary Astronomy" (GA 323)

The following are edited transcripts of

’s introductory remarks at six of our Urphänomen reading group sessions that began back in August 2023. I’ve included some screenshots of the slides I refer to, but most of them were animated in the live presentation, so you’ll have to watch the embedded videos to see the full context of my remarks.Lecture 1 (Link to Steiner’s Lecture)

The lectures collected as “Interdisciplinary Astronomy” (GA 323) were given in Stuttgart in January of 1921, beginning January 1, New Year’s Day, and moving through the 21st.

Steiner tells us, first of all, this is not a lecture cycle just on astronomy. It’s really more about interdisciplinarity, or nowadays, I think we would even say transdisciplinarity. He’s trying to get scientific specialists to break out of their silos and begin to talk to one another. He thinks we need entirely new metaphysical categories that would allow us to connect what we study in astronomy to what we study in physiology, and both to what we study in epistemology. We need to be able to think these various branches of modern science as part of the same universal tree. Unfortunately, as universities became more professionalized and disciplines split from one another and started developing their own jargon, they became kind of self-perpetuating. We have a proliferation of specialized knowledge about more and more, but it’s all less and less connected. It’s as though universities are producing a kind of knowledge that has nothing to do with the universe. It’s an abstract knowledge, estranged from life.

Steiner points out that pre-Copernican astronomy had a very different relationship to the sky. Pre-modern peoples, including astronomers, astrologers, and philosophers, related to the stars as individualities.

Steiner frames this new modern approach to science as being developed based upon certain faculties in ourselves. This need, Steiner says, for clarity and distinctness, these are sort of the calling card of Cartesian epistemology. It’s all about finding ideas that are clear and distinct. The other aspect of this modern approach to knowledge, Steiner says, is that we seek out this inner compulsion we get from chains of unassailable logical reasoning. When we have clarity and distinctness and a sense of a chain of logical deduction that pulls us along, then the modern mind feels comfortable. This is the age of the Consciousness Soul. These are the sorts of faculties that make us feel safe and secure. But his point here is that what we think of as a mechanical universe out there has really nothing to do with the actual universe. It has more to do with the kind of consciousness through which we are apprehending it and the faculties that we’ve developed at this time to apprehend it. But he says we need to move beyond this. We need to recognize the way in which, as he puts it, we spin a mathematical and mechanical web over the data, over the phenomena. We need to return again to the phenomena and recognize how these two poles in our knowledge of the universe, namely astronomy and embryology, are actually intimately connected.

It’s easy, as Steiner repeats again at the beginning of this lecture, for us to mistake the model for the reality. What I’ll show you is a kind of model that just helps us visualize the rhythms, but it’s potentially misleading if we try to get a flattened, two-dimensional representation of what are really the living movements of intelligent spheres, the visible gestures of spiritual beings. When we try to flatten this out in a way that our spatializing mathematical imaginations can grok, we capture something interesting but potentially lose sight of the concrete reality. So, just keep that in mind.

Steiner, at the beginning of this lecture, is reminding us what everybody knows, or pretty much every astronomer at this point knows, that Copernicus’s model is inadequate if we think it’s a mapping of the real facts. If we’re just looking for a practical way of correlating observed facts, Ptolemy’s model is just as good as Copernicus’s. Actually, it was more accurate than Copernicus’s. Kepler and Newton needed to tweak it to make it as accurate as Ptolemy’s model. Steiner’s concern with contemporary astronomy is that it’s conflating the models with the real facts and becoming increasingly difficult for modern astronomers to reconcile the model to the reality. Contemporary science leaves the human being out, and we have to put the human being back into the cosmos before we can actually, in a participatory way, understand the gestures, the rhythms that we see traced in the heavens, and that we ourselves, as living organisms—not just physical beings but etheric, astral, and spiritual beings—are participating in.

Our human body becomes the instrument that Steiner wants us to tune to these celestial rhythms. We’ve become so accustomed to thinking that, oh well, when you do astronomy, you need a telescope. He’s not saying we can’t learn anything from telescopes, but he’s saying we have an instrument already. It’s fallen into disrepair for most of us because we’re taught that there’s nothing we could possibly learn about the real facts by tuning into our subjective experience. Steiner says no, we need to perfect this instrument.

When we look at the heavens through our physical sense organs, they appear to be separate from us, independent from us. Their movements have nothing to do with our daily rhythms, annual rhythms, monthly rhythms that we experience more directly in our living organism. Our eyes make it seem like those are just bodies really far away in external space, and that’s a kind of illusion. What our eyes show to us very clearly and distinctly is a kind of illusion. There’s a subtler form of perception, a supersensible perception, that Steiner is trying to wake us up to. He’s pointing out that this is the direction astronomy would need to go in the future to grant us more concrete knowledge and understanding of the heavens.

There’s a lot of work to do, even if we understand cognitively what he’s suggesting that we do to change our methodology. He points out, just another example, how science has become so abstract. Geology and mineralogy study the Earth as though it were just a physical being, which leaves out the plant realm or the etheric realm, the animal realm or the astral realm, and the human realm or the spiritual. The concrete Earth, the true Earth, is not just a rock. It’s a living, ensouled, divine being. If we want to understand the Earth’s position relative to the other spheres of the cosmos, we need to consider it in all its dimensions. We can do so again by bringing ourselves, our full humanity, back into the phenomenon that we are trying to observe. We are part of the phenomenon we are trying to observe.

He talks about how plants are more intimately connected to the heavens than just the mineral realm, and that vegetation is the kind of sense organ of the Earth. It opens its eyes to the cosmic forces in summer and closes its eyes in winter. He talks about this polarity of exfoliation as a result of the sun forces meeting the plant world, and then the Earth forces, as the Earth kind of tilts away from the sun, pulls the plant realm back into a contracted, seed-like state. He asks what etheric space is like. It has a qualitative polarization, and it’s a process, rather than a physical space. It’s a kind of polarized process of spatiation, where the plant realm is expanding and contracting in relationship to the solar and terrestrial forces.

He’s giving us a hint here into what a qualitative astronomy would look like, considering more than just the physical dimension but also the etheric. Then he goes on to talk about the astral layer of the Earth, which he is linking to the diurnal rhythm, related to the interactivity of the human soul. The diurnal rhythm is related to our inner soul life, and the annual rhythm, he says, is more related to our physical growth processes, particularly the first seven years of childhood development and the way that the skull is shaped. This physical process of formation and growth in our bodies is more to do with this annual rhythm of the Earth in relationship to the Sun, whereas the inner soul life has more to do with the diurnal, daily rhythm.

He brings in the lunar forces and the 28-day cycle, another rhythm especially connected to the bodily processes of female organisms, at least those animals which menstruate. The male organism still has this rhythm; it’s just kind of more subtle and etheric. He connects memory to menstruation in a very interesting way. He says that just as menstruation is this kind of cosmic rhythm that is free from the cosmos, from the lunar rhythm—in other words, the cycles of the moon are the same time frame as the menstrual cycle, but the menstrual cycle has been individuated; it’s not always in sync with the moon. In the same way, our memory, we don’t need to observe the event which produces the memory at the same time; we can remember later. There’s this kind of analogy that he’s making, which astrologically connects memory and menstruation and the body, and all these things are connected to the moon. This was helping me understand some of these subtler archetypal correlations that astrologers talk about. Steiner’s giving us a very concrete sense of why these things are connected.

Then he talks about the Saturn cycle, this 28-year cycle, which is in some special relationship to the 28-day cycle of the moon, but again, having more to do with the development of our physical bodies. He’s trying to give us a sense again of how a qualitative astronomy, that puts the human being in all our layers—physical, etheric, astral, and spiritual—back into the cosmos as a legitimate organ of perception, an instrument by which we might come to deeper knowledge of the world around us. He’s just giving us some hints as to what this would look like.

He ends this chapter talking about how Kepler still had an intuition of this universal life, of the movements of the planetary spheres as meaningful gestures, rather than just isolated bodies obeying a fixed law of gravity as Newton had it. The mathematics, I admit, was a little bit beyond me, but I kind of had an intuitive feel for what Steiner was describing there about the difference between Kepler’s view and Newton’s view.

Good morning, good afternoon, good evening. We are on lecture five. I found this lecture to be especially potent. Steiner’s been building up to a moment, laying out some presuppositions for us, and now in this chapter, he’s really giving us a sense of the inversion he’s trying to affect in his Goethean approach to astronomy.

The key issue here for Steiner is that we need to let go of this desire to find a better model as though the goal here would just be to replace the Copernican model with a more mathematically or scientifically adequate mechanistic picture of the cosmos. He’s making sure that we understand that we’re never going to be able to fit the heavens into our head. In other words, we’re never going to be able to intellectually figure out in a mathematical way how to compute the motions of the heavens because inevitably we run into irrational numbers. Instead of a new model, he’s trying to coax us into a different feeling for the cosmos, a different way of relating to the phenomena that would not simply be through our sense organs and our ideation or intellect.

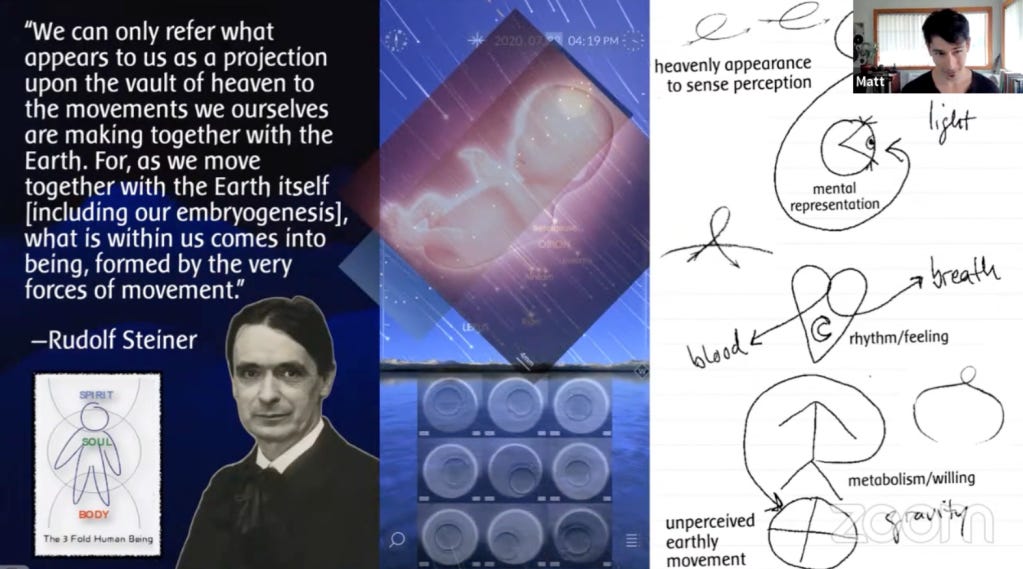

He then goes into his threefold picture of the human being. I want to actually share my screen and draw a little picture to capture this, but his basic idea here is that the threefold human being and the various organ systems that establish our humanness are internalizations or in some kind of rhythmic participation with the broader cosmos. If we want to understand the cosmos in its totality concretely, rather than just making pictures of it in our head, then we need to understand the way in which our full human composition – physical, etheric, astral, and spiritual – and the way that our various organ systems are in some ways in correspondence with aspects of the universe.

Steiner talks about the nervous system and the senses, the rhythmic system – the heart, the lungs – and the metabolic system and the limbs, and the ways in which these different systems relate us to the cosmos. He describes this inward movement related to the nerves and senses and then describes a kind of outward movement related to metabolism and the limbs. [Draws a body without a head, and then adds a head.] In between is the rhythmic system, which is sort of mediating between the inward and outward movements. With the head and senses, we get the cosmos streaming into us, and then we go to work on this with our ideas, with our thinking. Whereas in our metabolic system and limbs, he says there’s a kind of analogy between the role that ideas play in our thinking and sensory life and the role that fertilization plays in the metabolic system.

Steiner says that it’s much easier for us to bring consciousness to the relationship between our breathing and our blood flow and to our thinking and sensing. So, it’s much easier to illuminate this relationship with our consciousness. But when we try to turn our attention to the metabolism, things get hazy. Steiner often says we sleep in our will, and so it’s much more difficult for us to understand what’s going on at the level of metabolism and this function of fertilization, which ties us back into the cosmos. Our ideation pulls us deeper into ourselves, whereas the sexual reproductive process pulls us back into the earth.

Steiner says there’s a kind of chaos that we discover at either extreme. When we take in the motions of the heavenly bodies through our senses, there’s something about the beauty of that scene that leads us to believe there must be some order at work there. But then when we go to work with our thinking, trying to calculate a model that might explain that order, we end up with these irrational numbers and arrive at a kind of chaos. Similarly, the inverse of this occurs when we look at the embryological process of fertilization. There’s a sense in which we move from a chaotic state, an unformed state, into something that’s more ordered and more amenable to a kind of geometrical, even mechanical study. The ovum itself, as it begins to divide after being fertilized into the human form, is something that seems to come out of chaos into order. Whereas when we look at the heavens, there seems to be an order displayed, but as we reflect on it more and more, we discover it leads to chaos.

So, somehow we need to find and cultivate an organ of perception that would be something like what the ancient Indians developed through their yogic breathing techniques, which Steiner associates with attempts to balance the rhythms of human perception with the rhythms going on in the cosmos. To develop a sense of spiritual perception of the cosmos as a whole. But he says we’ve outgrown this particular approach. We modern Westerners can’t do what these ancient Indian practitioners did with their breathing techniques. We need to cultivate a new kind of organ of perception.

I thought of a neat connection here between Steiner’s claim that basically astronomy is deficient in reality, whereas embryology is deficient in concepts. There’s a way in which our sense perception and intellectual reflection upon sense perception remains too abstract and removed from the real. Whereas our metabolic and will life is so immersed in the real that we don’t have adequate concepts for it. There’s an interesting correlation here with Whitehead’s theory of perception that I just want to share briefly.

One of Whitehead’s important innovations in his study of the history of philosophy, something he is very critical of, and something he introduces to try to bring philosophy back to its senses, as it were, is he distinguishes between two modes of perception. One, which he calls presentational immediacy, would be akin to what Steiner talks about just in terms of sense perception. Empiricist philosophers would describe our sense perception as giving us primarily kind of patches of color that then the mind goes to work associating. Ideas for the empiricists would just be faded impressions. But even the rationalist philosophers still construed sensory perception in this way, that our most immediate, primordial means of accessing the external world is just through the five senses. That’s the basic idea that all modern philosophers, rationalists, or empiricists, would accept, even if the rationalists and empiricists have some differences of opinion about the role that thinking might play in ordering those sensory perceptions.

But what Whitehead introduces is this other form of perception, which he calls, instead of sense perception, bodily reception or perception in the mode of causal efficacy. It’s that part of our experience which we barely notice because we’re so focused on our sensory experiences. We barely notice the fact that we have this deeper visceral experience, which he identifies with causality or causal efficacy. It’s this reality principle that puts us in touch with the rhythms of the cosmos around us. But because these rhythms are generally much slower and change less in comparison to what we see with our eyes, which is constantly changing, so it captures our attention. Whereas these deeper rhythms, which Whitehead’s not as explicit about, but Steiner really describes these deeper rhythms quite concretely. The lunar rhythm, for example, or the day-night cycle, our experience is obviously deeply affected by the shift in light during the course of a 24-hour cycle. These deeper rhythms of feeling are part of what Whitehead calls causal efficacy, and it’s part of what modern philosophy and science have totally ignored in their study of the universe, and instead focused only on sense experience and developing instruments which extend that sense experience. Then, of course, developing all sorts of abstract models meant to explain that sensory experience.

So, it’s as if modern science and philosophy have been operating in an attempt to understand the universe as if the human being were just a head with no body. I think what Steiner is inviting us to discover is very similar to what Whitehead was attempting to do, bringing our attention back to bodily perception of these cosmic rhythms. If we want to understand the universe as a whole, we need to develop a new kind of science that would be attentive to these subtler rhythms not discoverable through our outward-facing senses.

I’m going to do my very best to summarize this chapter as a non-mathematician. As Steiner has been reiterating in many of the previous lectures, he really wants us to be very careful to remain within real concepts and not allow ourselves to spin webs of thoughts that are disconnected from experience. In astronomy, we’re inevitably going to be using figures, forms, and numbers, but he says that because of the incommensurabilities, for example, of the ratio of the revolutions of the planets, we’re going to need to strive for something qualitative, even within this mathematical approach.

Astronomy can only give us mere images, and to understand those images, we need to understand the nature of the human being. But first, he introduces what he calls some “graspable ungraspable” ideas: Cassini curves. Steiner introduces ellipses and hyperbola, and how we can move from an understanding of ellipses, which have to do with a constant sum, and hyperbola, which have to do with a constant difference, to the idea of curves of constant product. This form of mathematics was developed by Cassini, a French-Italian astronomer and astrologer for King Louis XIV. He was observing the rings around Saturn and grappling with Kepler’s new understanding of planetary orbits as ellipses. He convinced the Basilica in Bologna to allow him to erect some equipment to create a camera obscura to track the image of the sun on the floor of the Basilica over the course of the year, seeing how it would shrink and grow as a confirmation of the Earth’s elliptical orbit around the sun.

Cassini was quite an able mathematician. He wanted to understand the rings of Saturn and tried to develop some mathematics for that. He also built powerful telescopes for his day and was the first to discover a gap in the ring of Saturn and to observe Saturn’s 7-year seasonal cycles, which have to do with its axial tilt.

He developed the mathematics of Cassini ovals, which I’m going to show you an animation of here. [Shows animation from Wolfram’s website.]

Steiner explains the mathematics of this, and I needed to see it animated to grasp it. There are footnotes in my edition that indicate when Steiner is pointing at various aspects of the curves he’s drawing, but this was really helpful for me.

What I really want to focus on is Steiner’s indications for how to move beyond just the forms and figures of mathematics into a qualitative appreciation for the relationship between our own ideational and imaginative inner life and the mere images that astronomy can give us. He says we need to understand how images arise in human beings to bring those mere images into some conception of reality. Mathematics itself provides us with facts that oblige us to leave space if we want to preserve the continuity of mental representations.

We must somehow leave space behind if we want to orient ourselves properly. The underlying structure of the human organism is of such a nature that it cannot be comprehended solely in anatomical terms. Just as we’re driven out of space by the Cassini curve, in contemplating human nature, we’re likewise driven out of the body by the mode of contemplation itself. We’re driven out of the realm that can be grasped empirically by the physical senses.

Steiner ends this chapter with interesting lines, saying, “Instead of looking at the human form from in front, they look at nature from behind.” This is how scientific materialism arrives at all its various theories concerning human nature. The typical approach to astronomy and natural science brackets the human being, does not consider human nature, does not consider the nature of the one doing the observation. When materialism puts the human to the side, we end up looking at nature from behind.

Consider Plato’s problem of the planets. When we look at the heavens from our perspective on Earth and observe retrograde motion, it can be thought of as seeing the backside of an embroidered pattern, which can look chaotic. To get the proper perspective that the cosmic artist intended, we have to look at the embroidery from the other side. This topological inversion is what Steiner is inviting us to consider.

When Steiner refers to the need to put the human being at the center of astronomy and to understand the nature of human ideation as intimately linked to the images that our physical eyes show us in the heavens, he’s indicating something very similar to what Plato was getting at with his metaphor of embroidery in Timaeus. We need to see the embroidery from the right side, rather than trying to construct hypothetical models that would explain the chaotic motion we see with our physical senses.

Steiner says that it’s typical for contemporary scientists and astronomers, and the educated public generally, to say that the geocentric Ptolemaic model of the solar system was this childish view that’s merely an appearance, and that we now know that the reality is something more like the Copernican heliocentric model. But then Steiner says that astronomers, if they’re honest nowadays, will say that the Copernican view is also a model and doesn’t actually capture the real motions. So, there’s still a gap in our understanding, such that we can’t quite calculate the true motions.

You can think of either the Earth as the stationary center with everything else moving around us, as depicted in this animation, or you could view things with the Sun as the still center with everything moving around it. Both of these are actually appearances, whether we make the Earth stationary or the Sun stationary. The reason they’re both appearances is that everything’s moving. These are oversimplifications of the reality.

Steiner says that both models are actually too craniocentric – headcentric – based only on what we see with our physical senses and the models that we can construct intellectually through our mental representations, imagining that something we don’t perceive could be reconstructed as if it were something perceivable. What’s missing here is, Steiner says, that materialism is not taking our own motion into consideration. You might think the Copernican model that throws the Earth itself into motion is taking our own human motion into consideration, but he’s talking about a subtler form of motion, a more organic motion: he means embryogenesis and our own metabolic activity.

Materialism does not take the motion of growth into consideration because it uses fixed forms of geometry, whether Euclidean or higher-dimensional geometries, that can’t capture the organic aspect of the cosmos. It is imagining the heavens as though they were just governed by gravitational force, as though they were just governed by mechanical laws, as though there were nothing creative or organic about these motions.

So if we were to bring the human Gestalt to bear on this, if we were to try to look at the solar system and its movements not just from a craniocentric point of view, what would happen? Steiner says we can view the motions in the heavens as a kind of projection of the movements that we ourselves, together with the Earth, are making. But these movements have to include embryogenesis, not just our physical movement but our organic movement.

As we move together with the Earth itself, including our embryogenesis, what is within us comes into being, formed by the very forces of movement in the heavens. So in the middle here, I’ve got this symbolic animation. I don’t mean this to be depicting with any precision how the growth of the human fetus is related to the movement of the sun in particular or the other planets. It’s much more complicated than this, but there is a basic correspondence, Steiner thinks, between this lemniscate pattern and the polarity in the human Gestalt between the head and the limbs, the radial limbs, and the spherical head.

Down below here, we have an embryo dividing in a Petri dish, and on the right here, I’ve superimposed Steiner’s account of the retrograde motions of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, which he describes these looping patterns for us.

Steiner then describes human perception and makes an analogy between how we can observe through our senses what is going on outside of ourselves, but that we can’t really observe what’s going on inside of ourselves, our bodily organs, for example, our liver, and so on. We seem unable to access consciously the perceptions that those organs might be having, whereas we can perceive what’s going on outside of us. He analogizes this to the unperceived movement of the Earth and also the unperceived movements of growth that contemporary materialist astronomy is unable to recognize being projected into the motions of the heavens.

Steiner goes on to describe the human form itself as a kind of open lemniscate, with this looping pattern you can see in the middle on the left of my drawing here, where you see the head as the closed loop and then the limbs are the open part of the lemniscate. He talks about the rib-vertebra pattern as another kind of open lemniscate. Try to feel into the way that your ribs meet at the sternum and then loop back around through the vertebrae. You get a kind of lemniscate pattern, which Steiner describes as also being present in the relationship of the afferent and efferent nerves.

As you move up the spine towards the head, this lemniscate closes; as you move down the spine more towards the limbs, it opens out. He says there’s quite a bit of metamorphosis going on as you move up and down, not only in the shape of the lemniscate but in its angle, which is less the case in animals, which have fewer metamorphic modifications in this respect.

Steiner then ends this lecture by describing the difference between the geometry of rigid space, Euclidean geometry, versus this more mobile conception of space, etheric space perhaps, that he’s trying to invite us into, where space would be grasped as a process – spatiation – that is more akin to the unfolding growth patterns of embryogenesis. But if we just think in terms of the sort of rigid space model of materialist astronomy, it’s very difficult to keep track of the various forms of movement that we can measure the Earth undergoing. There’s the rotation on its axis, there’s the revolution around the Sun, there’s the precession of the axis, there’s the axial tilt variations, there’s the apsidal precession, there’s the orbital inclination, there’s the movement of the solar system around the galaxy, and the movement of the galaxy itself.

As we go out and out through this more materialist approach to astronomy, we’re still looking for that outside perspective, as though we were just heads floating in space. We go back to the cosmic microwave background radiation, and for Steiner, we’re reaching in the wrong direction when we do this. But even in contemporary astrophysics, there’s this recognition that the universe itself is in a process of growth and development. Whether the Big Bang is the right way of thinking about this or not, there is undeniably some sort of time-developmental process underway.

When we do go out to the cosmic microwave background radiation in search of this craniocentric explanation of everything, there’s already this hint that, okay, this is an expanding process. There’s something growth-like about this. Even in astrophysics today, I feel like science is right on the verge of recognizing this need to shift from the quantitative to the qualitative. As Steiner has described in earlier chapters, embryogenesis moves out of chaos, something incalculable, as the embryo divides. Cell by cell, it becomes calculable; you can count the number of cells. Whereas the inverse is true of astronomy, it appears calculable at first, but as we take our perspective out and out to consider more and more of these motions, we end up with these incommensurabilities, incalculability, irrational numbers.

This is why Steiner is trying to bring these two sciences together. He says if we develop a feeling for morphology in a higher sense, we can only ascribe the human Gestalt to the solar system. There’s a projection of the human constitution onto the cosmos. We need to develop this more organic perspective that considers not just our physical motion but our organic motion, our embryogenetic motion.

I think Steiner gives many indications here. I’d also highly recommend Karl König’s “Embryology and World Evolution,” where he looks at Steiner’s Outline of Occult Sciences but also does his own reading of the Book of Genesis and looks at some of the correspondences he sees between that and the process of human embryogenesis, and tries to describe how, with the growth and development of each individual human being, there is a recapitulation of the development of the entire cosmos through its various Saturn, Sun, Moon, and now Earth phases. Embedded within our own patterns of growth is this memory of the whole of creation.

To understand the historical unfolding of solar system dynamics, we need to think not just spatially but also temporally and to feel that history in our own organic patterns of growth. Rather than just imagining ourselves as heads floating in space, searching for the true Euclidean motion or even if it’s Riemannian or Minkowskian geometry, we’d still be, in a sense, floating heads. We must instead try to understand a motion that is far more embodied and etheric.

I wanted to start with an anecdote that Elizabeth Anscombe, one of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s students, related in some biographical writing she did about Wittgenstein, who was her professor. He once asked her, “Tell me, why do people always say that it was natural for men to assume that the sun went around the earth rather than that the earth was rotating?” Anscombe answered, “Well, obviously, because it just looks as if the Sun is going around the Earth.” To which Wittgenstein replied, “Well, what would it look like if it had looked as if the Earth were rotating?” This somewhat elliptical story, this exchange between Wittgenstein and Anscombe, shows the subtle ways that thought participates in fact, the way that phenomena and theory relate.

Steiner wants to draw our attention to what we actually observe. Whitehead introduces his theory of perception by reminding us that false interpretations of observed facts enter into the records of their observation. Thus, both theory and received notions as to facts are in doubt. Steiner begins this chapter by reminding us to really attend closely to what we observe. He says the Ptolemaic and the Copernican systems are both attempts to synthesize the phenomena that are observed, to comprehend with certain mathematical figures what has been perceived. He adds parenthetically, “I say perceived because it would not be enough to say seen,” where perception here is distinguished from seeing due to its having some mixture with concepts and with thoughts.

Steiner continues, “for it is precisely observation upon which all our geometry, all of our calculating and measuring, must ultimately be founded.” At bottom, the only question is whether we are comprehending the observed facts correctly. He adds that the sciences, modern science, materialistic science, as currently practiced, takes perception at face value.

Steiner then talks about the example of a cartoon drawing of a horse. The motion of a galloping horse is a mere appearance: we’re really just looking at a series of still frames. He points out that from the Copernican point of view, when we observe the position of Mars night after night, we’re getting a kind of snapshot, and in our theorizing about this, we add with a kind of mathematical line this motion, but it’s a kind of cartoon image of the heavens. He’s saying it’s like the night sky is a kind of cartoon flip book.

Steiner says we want to be scientific, which means we have to attend to the material of observation, but the Copernican approach has been observing only with our physical eyes and has been seeking to translate this mere visual perception into a rigid geometrical model. Time, meaning concrete time or duration as Bergson would say, and therefore also real motion, living motion, is not measurable, it’s not calculable.

Whitehead helps us understand this with his account of perception in terms of two modes. There’s perception in the mode of causal efficacy, which he also refers to as non-sensuous perception of bodily feelings of moving out of the past and into the future. That’s our perception of time through causal efficacy. Then there’s perception in the mode of presentational immediacy, which is dominated by visual perception of space.

Whitehead says the separation of the potential extensive scheme into past and future lies with the mode of causal efficacy and not with that of presentational immediacy. The mathematical measurements derivable from presentational immediacy are indifferent to the temporal distinction between past and future, whereas the physical theory expressed in terms of causal efficacy is wholly concerned with it. It is wholly concerned with this causal efficacy, this passage from past to future.

Steiner talks about the three-body problem, making a playful analogy to a problem in Newtonian physics and trying to understand the chaos that is unleashed by the trajectories of three bodies. He makes an analogy to a sort of spiritual-scientific view of these three bodies, the Sun, the Moon, and the Earth, and talks about how we really can’t imagine the relationship between the kingdoms of nature (minerals, plants, animals, humans) in a linear way. He says we have to imagine an ideal point from which the development bifurcates into one branch that is longer, arbitrarily long, where the Sun and its relationship to the Earth bring forth plants, and that plants are driven by the terrestrialization of solar energy into this mineral form.

Steiner talks about the negative indetermination that leads to the human being. By negatively indeterminate, he’s talking about a path of development that is not defined by a linear progression or qualities that can be easily quantified. He’s saying it doesn’t follow a predictable positive determination towards complexity.

Steiner describes how the Moon is in reality a nexus of forces that’s pervading us all the time and that what’s visible to our eyes is no more than a fragmentary revelation of cosmic space, which in reality is filled with qualitatively differentiated subtle fluid of sorts. He makes an analogy between the Moon-Earth system and a gamete. The Earth and the Moon are two aspects of a single process, a single organic whole.

Steiner says that the Moon is a visible sign that points us to the fuller reality of this Moon organism that we are inside of. These bodies are not out there in space; we are inside of them.

Steiner contrasts this with the modern Copernican model, where we are living inside a model of the universe constructed out of visual sensations and measurements and rigid mathematical models. He says after the feeling of original participation had faded, the inward bodily feeling of being immersed in the Moon was completely lost. Today our experience has become restricted to that of the illumined image.

Whitehead emphasizes that the body is subtly extended into and inseparable from its environment. Whitehead says “the first error of modern scientific epistemology is the assumption of a few definite avenues of communication with the external world.” He goes on to say that “the living organ of experience is the living body as a whole. Every instability of any part of the body imposes an activity of readjustment throughout the whole organism. We cannot determine where the molecules of the brain begin and the rest of the body ends. Further, we cannot tell where the molecules of the body end and the external world begins. The truth is that the brain is continuous with the body, and the body is continuous with the rest of the natural world. Human experience is an act of self-origination, including the whole of nature, limited to the perspective of a focal region located within the body but not necessarily persisting in any fixed coordination with a definite part of the brain.“

Whitehead also emphasizes that “the predominant basis of perception is perception of the various bodily organs as passing on their experiences by channels of transmission and of enhancement.” He criticizes “the accepted doctrine in physical science that a living body is to be interpreted according to what is known of other sections of the physical universe. This is a sound axiom, but it carries with it the converse deduction that other sections of the universe are to be interpreted in accordance with what we know of the human body.”

Steiner concludes by calling for a shift from a modern, mineralized science ruled by the tyranny of the eyes and the sense-bound brain to an etheric science that’s freed by an open heart to perceive the true movements of the living spheres, which are not separate from the true movements of our own living bodies.

Steiner begins this lecture by referring to the “so-called body of the Sun,” which if you look in any science textbook nowadays, the Sun will be referred to as sometimes just a ball of flaming gas, which even scientifically is incorrect, but it’s been hard to shake that description. There’s a fourth state of matter called plasma, so when the scientific account is more accurate, they would say it’s a ball of plasma, and there are all these interesting magnetic effects, sunspots, and a lot of mysteries that astronomers, heliophysicists, admit–there’s much they don’t know. But scientists have sent these probes up to observe the Sun; it’s constantly now under observation by all of these various instruments, looking at different wavelengths of light and collecting all this data. But the question is, is the theory we’re using to interpret all the data correct? Steiner would say no, because we are applying terrestrial physics to something which is not terrestrial, not made of the same kind of matter that exists here on Earth.

Steiner challenges us to throw off the shackles of existing theories. He says that the existing theories of the heavens, of astronomy, of cosmology, these theories are like shackles lying upon the facts. The challenge here is to really observe without our observations being sort of predigested for us by a theory that we were taught in grade school before we even have had a chance to actually observe for ourselves using our human senses. We’re given a theory for what the Sun is, and if we don’t observe or question, we go through life imagining that that theory was the truth. Even from a scientific point of view, if one were to be strictly scientific, one would want to question all existing theories and really make sure that they fit the observations. In cosmology, there are so many examples of observations and data points that don’t fit the existing theories, but because the theories have become so institutionally entrenched, they can’t be falsified; they can’t be challenged. But Steiner presents this picture rooted in a new approach to natural science, which is Goethean, meaning instead of trying to build up more and more models, more and more accurate models of phenomena, the Goethean approach would, as far as possible, want to do away with hypothetical models to just leave us with properly arranged phenomena. Properly arranged phenomena, properly organized phenomena or facts, would show us their own theory; the theory would simply be the facts perceived in a rightly organized series.

Steiner presents this picture of the Earth and the Sun as two spheres that are thrusting into each other, and he describes Earthly matter as having a positive force, a physical outward pressure, and solar matter, as a negative force, that has a kind of etheric inward suction. He thinks that many phenomena, including comets, light and heat and so on, have to be reimagined in connection with this interplay between the earthly physical and the solar etheric forces. He describes the Sun as a concrescence or a gathering of suctional forces and as a hollowing out of space itself–not just empty space. It’s not just that the Sun is hollow, which is sometimes how his view is summarized or caricatured. It’s even emptier than empty space, he says, so it’s “less than empty.” He thinks that this provides an explanation for what we call gravitation, that no other idea can hold the various phenomena together.

I want to interject a Schellingian point of view here for a minute. I couldn’t help but think of Schelling’s natural philosophy while reading Steiner. Schelling wrote this text, “On the World-Soul,” in 1798, and at the time, he was in deep dialogue with Goethe. He had already written another book on natural philosophy called “Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature,” which Goethe read and appreciated. But in dialogue with Goethe, Schelling was being lured away from a more idealistic point of view into a point of view on natural science which would do justice to experience and to really move away from the idea that one could know the truth about nature purely through a kind of a priori transcendental reflection; as if, from the Kantian point of view or even the Fichtean point of view, nature would be something constructed by the activity of the I. Schelling wanted to understand nature itself as a self-constructing process, and he drew on the ancient idea of the world-soul to do so. He describes light and gravity in a similar way to Steiner. He says “In nature, everything strives continually forward. We must seek for the reason that this is so in a principle which, as an inexhaustible source of a positive force, constantly instigates anew and uninterruptedly maintains the movement in the world. This positive principle is the first force of nature,” which he later says is light. “But an invisible violence leads all appearances in the world back in an eternal circular path. We must seek for the ultimate reason that this is so in a negative force, which by continually limiting the effects of the positive principle, leads the universal movement back to its source. This negative principle is the second force of nature,” which he later identifies with gravity. “These two striving forces combined together or set in conflict lead to the idea of an organizing principle, which forms the world into a system,” which he later identifies with the world-soul. So he’s talking about light as positive, gravity as negative. If we were to associate light with the Sun, Steiner is telling us that the Sun has this negative force. But it doesn’t really matter, I think the point here is that Schelling is recognizing this original antithesis in nature between these two forces, light and gravity, and the relationship between the two gives rise to the life of our solar system.

I can’t help but think of Steiner’s comment, which I’ll return to in a minute, about how there are these two tendencies in the movement of the planetary bodies. There’s this tendency to ossify, which is why we can make any calculations that are predictive at all, and then there’s this other tendency toward life, which is to break free of the purely repetitive, calculable motions, and to instead introduce this element of openness, of creativity, of life. Schelling is here describing something quite similar.

Schelling also refers to light as “negative gravity” at one point in this essay on the world-soul. I wanted to just make that connection here. I see Steiner very much carrying forward the Schellingian point of view and philosophy of nature.

Steiner then offers some mathematical analogies for those who might want a more mathematical approach to the ideas he’s presenting. He talks about the imaginary number plane and, he says, if we were to describe the magnitude of occupied space or ponderable matter as positive, empty physical space would then be zero, and this less than empty solar or etheric space would be negative. And then if we bring in the imaginary numbers, he says we can use this to represent astral materiality or spirituality, better said, which is quite interesting. Is this an analogy? Is he saying that we could be actually quite precise in mathematizing these different forms, these different forms of existence, of matter, the physical, the etheric, the astral? I’m not sure. I’m curious what you all think, because he kind of just introduces this as an aside.

He next talks about our sense of touch and shows how this polarity between the Sun and the Earth is present in so many other phenomena, and that the human being is in some sense shaped by the polarization of these two forces. He says “if we trace these things inwardly with the clear eye of the Soul, then we can begin to sense the opposition of Sun and Earth into which we have been placed as human beings in every act of sensory perception. Everything about our human nature can be traced in such a way as to perceive the workings of the cosmos within us. Cosmic forces influence human beings at every hand.”

He describes when we touch a material surface, that the pressure it exerts on us is earthly, an expression of the earthly force, but the counter-pressure that we feel in our own finger, he says, is the force of the Sun working through us. In other words, the etheric body counters the force of pressure from the external body which we’re touching. So this sensation of pressure he describes as a reciprocal effect of the Earth-Sun polarity. I think what he’s inviting us to experience here is the sense of our true bodies as being cosmic in their extent.

So just as the Sun and the Moon and the other planetary spheres envelope the Earth, they’re not just simply located where we see the point of light in the sky. Just as they are more like spheres that envelope the Earth, extending beyond just those illuminated bodies visible to our eyes, the real human body does not stop at the skin boundary but extends into cosmic space to encompass the entirety of the visible heavens. So during the day, as he rehearses for us in this final lecture, we stand vertically, we partake in the etheric circuit between the Sun and the Earth. Our head is filled with wakeful thoughts, and our willful bodies are enmeshed in the earthly metabolism. And then during the night, we lay horizontally, as if unplugging from the terrestrial-solar circuit, and our metabolism goes to work within our own heads, and we have more of an enclosed etheric body. So during the day, we’re connected to this larger Earth-Solar circuit and at night we seem to leave that circuit while our astral body and ego are quite expanded into the cosmos, with the etheric and physical body still laying there in bed.

Next Steiner once again tries to describe for us the lemniscatory path of the Sun and the other planets, sort of following along behind it, but you know, he points out even if we could draw this lemnicatory path perfectly, we would still never be able to finally come up with a model of the movement of the heavenly bodies that would be true for all time. He says no matter what mathematical curve I may devise, once it’s fixed and finished, the reality will certainly escape me. My finished curve won’t capture it. A planetary system tends in both directions, on one hand toward rigidity and on the other hand toward mobile lemniscatory movement. So as I said earlier, to some extent, the planetary system is subject to this ossifying tendency, otherwise none of our models—the Ptolemaic, the Copernican, Kepler’s and Newton’s—none of these models would be predictive at all. But there’s this other tendency, and so you know, as Schelling was describing, it’s as though gravity, this ossifying tendency, is met and checked by levity, by this etheric power which keeps the lemniscate open, fresh, alive. And I couldn’t help but think of the corkscrew growth of plants in this context, which are mimicking that same movement.

Now, maybe some of you have heard of the Electric Universe theory or Plasma Cosmology. I’ve gotten to be friends with and have studied very closely the work of a plasma physicist named Timothy Eastman, and through him, I have become quite skeptical of the Big Bang model, which is trying to explain the entire history of the universe only in terms of gravitation, as if only gravitational forces were operating. And it leaves out, Tim Eastman would say, the effect of plasma dynamics. And if we just bracket for a minute the 96% of the universe that cosmologists currently say is made of dark stuff that we don’t understand at all, and just look at that 4% which would be all the actually visible matter in the universe that we do say we understand with normal particle physics, 99.9% of that 4% of visible matter is plasma. And plasma is also, as I said earlier, what the Sun is normally described as, and that brings in these electromagnetic forces which can be formative forces, right? And what we’re looking at here is an experiment done by an astronaut on the space station using a knitting needle made of plastic, and you saw him rubbing it to create a static charge, and these are just droplets of water that begin to orbit through the electric field.

This is not gravitation. This is a different phenomenon, but I couldn’t help but wonder if this suction force that Steiner is describing in the Sun might have any relationship to these sorts of dynamics. I’ve talked to Gopi Vijnaya little bit about this, and he’s somewhat skeptical, but you know, you can see just the way that the water droplets move, it’s kind of tantalizingly similar to what we might want to imagine is going on with the Sun and the other planetary bodies. So I just wanted to throw that into the mix, and also in Steiner’s discussion of comets, there’s a little statement he says in this final lecture where he’s not saying that comets have no sort of material aspect, but there’s something else going on which, again in terms of plasma cosmology, we would understand as the effect of the Sun’s solar wind hitting the little bit of matter and ice and stuff that’s thought to be the nucleus of a comet and creating this huge tail, which is a plasma effect.

So when he talks about the comet coming into and out of existence, I just wonder if we could understand this in terms of a kind of plasma cosmology or if he’s talking about something else entirely. I’m trying to build bridges here between more established scientific understanding and Steiner’s esoteric view, though even within established science, the plasma cosmology perspective is marginalized because it’s challenging the gravity-only models of the origins and organization of the universe.

Steiner closes this lecture by talking about how we need new laboratories, and we should start with empty laboratories, throw out all the existing instruments, because he says today’s instruments can only yield what’s already contained in the physics textbooks. In other words, the instruments that we have nowadays—I mean, 100 years after Steiner, this is so much more the case—they’re so elaborate and complicated, and in so many ways, the theory that they are trying to test is already kind of baked into the design of the instrument, such that whether it’s a particle collider or the James Webb Space Telescope, it’s very difficult to actually make observations with these instruments that wouldn’t confirm the theory that led to their design in the first place. And so Steiner thinks in some ways we really need to start fresh, and this is a great benefit to spiritual scientists because we don’t need a huge multi-billion-dollar budget to try to out-complexify the existing instruments that Big Science is using. We can start with an empty room and our imaginations; and remember Goethe’s admonition, that the only truly neutral instrument in terms of not being sort of front-loaded by a theory would be the human organism itself. So the best instrument for observing nature is the human organism, with our suite of senses that everyone acknowledges, but also imagination, inspiration, and intuition. Steiner’s asked a question at the end of this lecture that he responds to: is this astronomical picture you’re presenting something that can be accessed and understood and verified if one has not yet cultivated these higher organs of perception? And he says, look, no, you can’t even understand the Cassini curves and the way that one goes out of space in these forms of higher mathematics without imagination. So you know, he’s clear that we do need to cultivate these higher organs of perception, but he also says that any insights provided through spiritual scientific methods could be tested against normal physical science, and they shouldn’t contradict. So there’s something that goes beyond the normal physical sciences, but should still be consistent with it. So that’s why I’m looking for these points of contact. He says, ‘You must have the courage to go beyond our existing judgments to develop the forces latent within the human soul or depth of reality will remain concealed.’

And then finally, he talks about the Kant-Laplace nebular hypothesis of the origins of the Earth and Humanity. Nowadays, we could think in terms of the Big Bang Theory as the modern contemporary equivalent of the nebular hypothesis, and Steiner is here very concerned about the modern split that severs the ethical from the physical dimension of the cosmos, such that human beings are left at the end of this process of blind forces churning, producing stars and planets and so on–human beings are left at the end of it as a kind of stranger in a strange land, aliens on our own planet. But Steiner points out in all of these materialistic theories there’s always the assumption of the perspective of the experimenter, the theorist, as if there’s a giant demon that exists outside phenomena that sets them in motion and watches them spin. He gives the example of putting drops of oil and water and then spinning that, and you know, you can produce what looks like planetary bodies orbiting the central point. In a lot of physics textbooks nowadays that introduce the Big Bang, you’ll see this guy blowing up a balloon to illustrate the expansion of space, which again, has human beings popping out at the end of it.

And the problem with this is it is a kind of demonology in denial because here we are at the end of it, imagining the origin as if we were there, right? And so we’re assuming the human at the beginning as a condition of the possibility of any theorization about natural phenomena, but then we’re also claiming that the human only pops out at the far end of this totally meaningless explosive process. And you know, instead of this inconsistency, we need to recognize that, yeah, the human being was there in the beginning, but the process that we are involved in is not just an explosion, it’s not just driven by blind forces, there are spiritual powers, spiritual beings at work, and we can participate with them in continuing to create this cosmos. I think that’s the invitation.